There are a lot of people who would say that what's happened to me shouldn't be happening. Or couldn't be happening. How can you have so few options for insulin? With patient assistance programs, coupons, copay cards, prescription discount cards, goodRx, Walmart - there's an option out there for me. People that work in pharmacy swear by it. Right?

The point of me being vocal about my journey isn't for you to judge me for how I've gone about surviving. I do understand that there's different ways to handle what has happened to me. My story is my own, though. This is what I've done to live. And the point of me being vocal is to point out the immense flaws in our system. I want to ask the deeper questions of why 3 drug companies raise prices on insulin yearly in conjunction with each other instead of being competitive and making sure that we don't need coupons and programs in the first place to afford our medication. I want to know why they blame rising costs on "research" but then publicly defame researchers searching for affordable cures and laud expensive, technology-driven systems that will keep diabetics coming back to buy more. I want to know why they claim generics are "too hard to make". I want to know why politicians feel like people with pre-existing conditions deserve to not have healthcare coverage or die because they were tossed a bad hand at genetics, in many scenarios. And I want to know why people are so passive about it. So here's a story about how you can end up being someone like me, and how you can fall through the cracks of the system.

I think that many of you know my story up to this point, and if you don't, much of it can be found on this blog. I was diagnosed at 17 years old, and two months away from moving out of state to college. My parents are divorced and my mother is self employed. We did not have health insurance back then and we were both relatively healthy individuals. I was very fit, not over 100 pounds until I was 15, and a competitive gymnast. We don't have a big family history of major health issues. My diagnosis took us all by surprise, and we were all very unprepared for the reality of life with a chronic illness. Including the $20000 hospital bill. This all slammed me like a train when I was being discharged from the hospital and told that until my medications were purchased, I wasn't allowed to leave.

"Oh." I told the nurse. "My dad will pay for it, I guess."

I'll never forget what she said next. "Oh, honey," she said, shaking her head.

"I don't think you realize how expensive this medicine is."

And she was right. I didn't. Thankfully, though, I did qualify for Medicaid due to my condition and my age. Medicaid covered my bill, pediatric endocrinologists agreed to see me under my health plan, and my insulin was covered without a copay each month. Was it ironic that I spent my life in high school denouncing programs such as Medicaid only to come to have my life rely on it? Yes. But working in healthcare, as well as having a disease of my own, I've certainly developed many new ideals and opinions when it comes to healthcare since then. My doctor prepared me for as long as I was able to keep Medicaid and see them. Until I was 21, I stockpiled insulin and I saved as much as I could. I knew the day was coming, and I wouldn't graduate college until 23, and start working until almost 24. How would I survive until then? I thankfully did - I worked, owning my own business, and I stockpiled more, and I found people - strangers, friends - who were able to give me what they had. In undergrad, I had to lie about my insurance so that I could still get Florida Medicaid as I was required to have health care at school. My Florida Medicaid didn't cut it, but if this was discovered, I'd be forced to by the school insurance since I wasn't a resident and had to live on campus, disqualifying me from residency. The school insurance wouldn't cover my medications. I put my info in every year, saying it was Georgia Medicaid, counting on the fact that Medicaid didn't answer the phone. Nobody bothered to verify the kind of Medicaid I had. So I was able to live like that until I went to graduate school. I lived off of stockpiled insulin, some expired, and was able to keep my Medicaid until that first fall, when I turned 21. The school insurance was so expensive, I'd have had to take out another loan to pay for it. An expensive private one, at that. So to cut costs, I continued to submit my old Medicaid information. This worked until my last year of graduate school, when they found out. They made me get the school insurance, then.

It had been 2 years since I'd seen a doctor at that point. Since I hadn't had insurance, I qualified for patient assistance programs. But to qualify, my doctor had to give me a prescription and fill out an application. I had never had a primary care provider, since my parents didn't have insurance. I didn't have an endocrinologist as I wasn't a pediatric patient anymore. And seeing an endocrinologist - a specialist - involved seeing a primary care provider, paying out of pocket, and then paying additional out of pocket for a specialist who required me to also get labwork - over $500-700, when all was said and done. So I went without, and opted simply for self-managing and paying for spare insulin from other people. When I was forced to get the school insurance, I made an appointment- a 4 month wait - for an endocrinologist. I paid my $250 copay and I saw him and I cried because I knew I hadn't been managing well. I was depressed. I was rationing. My A1C had creeped up since grad school. I was running out of insulin. I was not in a good place. My doctor helped give me the push to get back on track, and he got me samples. I couldn't afford my prescriptions because my school insurance didn't have adequate coverage, but I made it.

So how did I end up here after I graduated? I felt as though I did everything right. I selected the job with the better insurance. I came to love my job. 2 months in, I learned the company was pulling out of the nursing facility I was in, leaving me the option to stay on with the nursing home under the new company, or transition with the old company, but to an outpatient setting, which I don't like. My heart is in geriatrics. I love geriatric PT, and for a gamut of personal reasons, I do love the building I work in. It is a fast-paced, high admission facility with patients with a wide variety of diagnoses and is unlike a lot of other nursing homes. I love that about it, and I've learned a lot. The company that was taking over also offered me a considerable pay raise, so despite my reservations, I opted to stay on. It was November 1. I chose an Aetna plan for the last 2 months of the year, which covered my scripts with a $40 copay, but my doctor wasn't in network. So for open enrollment for 2018, I took the survey to recommend an insurance plan for me within network with my doctor. A UHC plan came up. Before you make any judgement, please bear in mind that these months were the first in my life that I'd ever had healthcare or selected health care plans. I didn't know much about it. The plan said it covered my prescriptions with a 20% copay, and I thought this sounded reasonable, and the premium was reasonable - my Aetna plan for two people was almost $650 a month. UHC's was closer to $400. So I selected the plan and figured I didn't mind the added expense. It wasn't until January when I went to fill my prescriptions that I learned that this applied after I met my deductible of $4500 for the year. The information about the plan stated it covered my meds, but I didn't realize this was after the deductible. This wasn't going to work. I desperately called and begged HR to let me change my plan. I tried to file an appeal. It didn't work. I was outside of the enrollment period, and this involved government rules. It wasn't HR just being jerks. I understood their hands were tied. I weighed my options. My choices were to find a new job and leave the one I loved, or stick it out. I made the decision to stick it out. Since then, I've been very vocal about the disparities and the underinsured in our system. I always have been - since my diagnosis - but especially now. I interviewed for an article with Bloomberg. I've posted on social media. I've reached out to Senators to laud for witholding the pre-existing condition mandate and holding drug companies accountable for their prices.

My recent social media post went viral and I received a lot of feedback about (more) use of coupons and patient assistance programs, all of which was greatly appreciated, as anyone seeking to help is always appreciated. Prescription savings cards aren't run with your insurance, so if a savings card saves you $100, but the cost of the drug is $500-600, this is still a great deal of money. I've applied to every coupon and savings program for all of the drugs I'm on, still to encounter this problem. Walmart insulin I wrote a post on a few weeks back which I'll refer you to. But in short, Walmart provides cheap insulin manufactured from the 80's. The Reli On, aka Walmart brand of insulins (novolin or humulin, I know they sometimes switch who they carry) are the older generation of insulins, and so they don’t provide quite the same coverage for blood sugars. They have a shorter half-life than name brand insulins. Their intermediate long acting has to be taken two times a day instead of one. 70/30 is an insulin they don’t even teach most patients to use any longer, because it’s outdated, and it has a high risk of causing increased hypoglycemia because it can be effective up to 24 hours with a peak effect at 2 hours. Not to mention the obvious, they're vials that involve the use of syringes, versus other more technologically advanced methods these days. Will they keep you alive? YES! Are they an awesome, state of the art method of giving you the best glucose control without giving you an increased risk for lows? Do they give you a good quality of life? No. They keep you alive. That is all. And I like being alive, but there is no denying it's harder to control my glucose on these medications, which I have used when I've had nothing else.

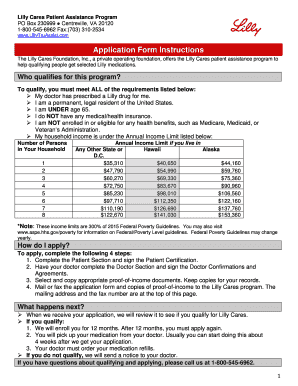

Now let's move on to patient assistance programs. I automatically don't qualify for patient assistance programs because of the fact that I have insurance, but a few people brought it to my attention that Lilly, one of the three insulin companies, changed their program to cater to individuals with high-deductible plans like me. So I promised I would check into it, hopeful again that this might help. It didn't take me long into the application to realize I'm well above the income threshold, posted here:

In case it's hard to see, here's the link. The income threshold for 2 individuals, as is the case with me, is $47,790 per year. The average salary for a physical therapist is $83,000/year.

That's plenty to pay for insulin, right? Let's break that down. For the record, I'm being transparent with this because I legitimately want people to understand what it's like to crunch the numbers for yourself. That salary listed above leads to an average of $3000/per 2 week. About $600-800 of that is taxed, and then another $250 goes to health insurance + HSA contribution. Rent is $1600, then there are utilities, insurance, streaming, groceries, has, etc. I pay a larger amount on student loans to avoid compounding interest because I don't want to pay them forever, so I pay about $1100 per month. I then work gigs with my own business to supplement my income with $1000-$2000 per month.

Now imagine your health insurance pays for... pretty much nothing. Insulin is $800-1100 minimum. Not withstanding other supplies. You do the math, and tell me how much money will get saved every month. I am not below the poverty level by a long shot. I'm well into upper middle class. But I'm in the 22% tax bracket. My insulin + additional diabetes supplies costs almost as much as my rent. Does this make sense to you now? Yes, I get it, get your priorities straight. What's $1100 compared to your life? But imagine going to school for 8 years. Working harder than anything to get there. Weigh my desire for financial stability, starting investments when I'm young, and taking mental health breaks and the occasional vacation to have time to relax from consistently working 5-7 days a week. I had my first day off in 2 months last week. 2 months. Am I wrong to occasionally splurge on myself? Am I wrong to want to save my money instead?

I would argue no. And to those who would say otherwise, I would say: shame on you. I have worked hard my whole life. I have sacrificed more than you will ever know or imagine to survive with a disease I never asked for. I never asked my pancreas to stop working. I also never asked myself to sacrifice my dreams because it stopped working, either. I would never ask that of someone. And neither should you. We as Americans should not have to make choices that sacrifice financial stability or rewards for our hard work for basic life needs. Insulin is not a choice. Insulin is a NEED. If I don't have it, I'll die. Period. If prices keep raising, I'll have to keep finding ways to make do. If insurance premiums continue to be unaffordable, I'll have to continue to make do. I will sacrifice these things if it comes down to it. It will be hard. There is no debate that I will do what it takes. But is that the way I want to live my life forever?

No. I've fought this battle since I was 17 years old, and I will always fight this battle. But it takes its toll on you. The lack of stability in my healthcare journey has been a hard one wrought with anxiety, depression, rationing, eating disorders, and the like. I know I am not wrong in wishing it was not this way. Just like I know I am not wrong when I say, again, that your coupons do not work. Your patient assistance programs do not work. Insulin/Pharmaceutical companies are using these programs as a guise in which to act as though they care about helping people like me without actually doing anything to help people like me. Too "rich" to qualify for help, to "poor" to afford my lifesaving medicines. Here is an idea instead, if coupons are that effective: make the medications cheap enough so that you don't have to use a coupon to pay for them. You'll save money not having to pay people to process the coupons in the first place. And, people like me could then afford them regardless. Until this change happens, though, I will not be silent. I will continue to fight in what I believe is the only sustainable, long term option: holding drug companies accountable for continual rising insulin prices. And I hope that reading this inspires you, too.